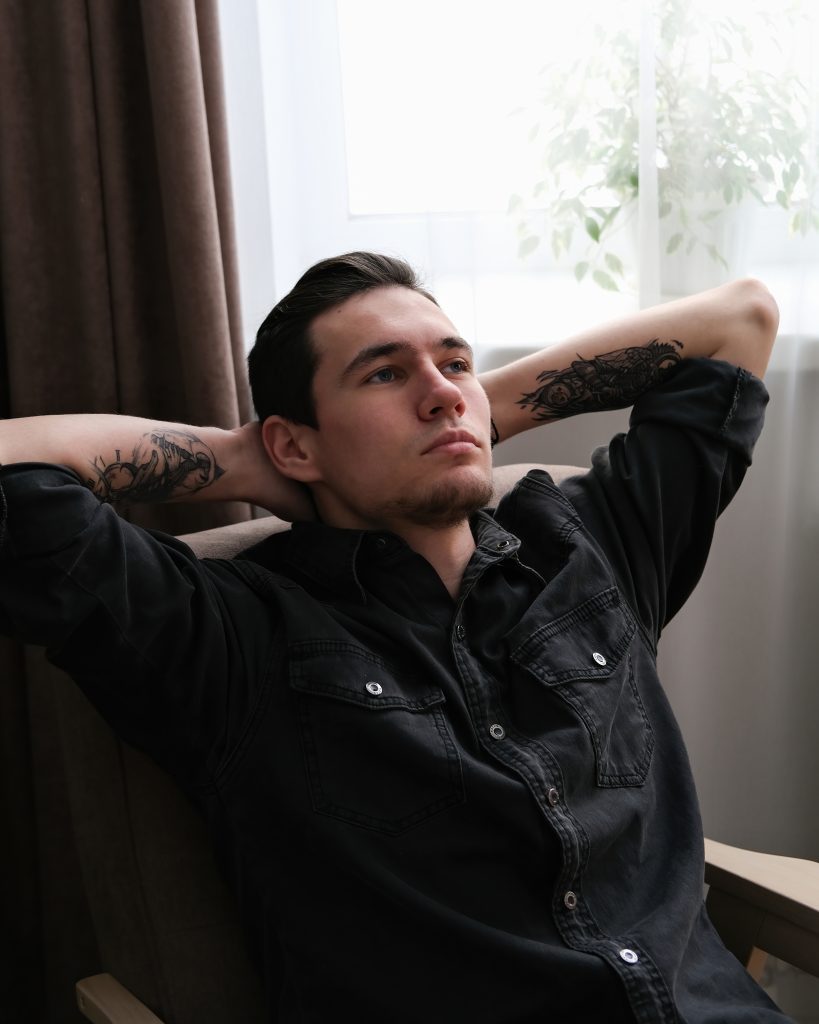

When depression goes untreated, it can lead to suicidal ideation (SI), a broad term that covers suicidal contemplations, wishes, and preoccupations with death and suicide. Looking for signs of depression in a loved one struggling with a chronic illness like dysautonomia isn’t overstepping a boundary or being judgmental. It’s part of caring for the whole person. If you are that person and have dysautonomia, then it’s important to address and treat your mental health concerns just as you would any other symptom.

Dysautonomia and Depression

DysautonomiaAs a chronic illness, dysautonomia brings its own unique challenges that can impact the mindset and emotional well-being of patients.

Multiple Symptoms: Dysautonomia patients often deal with multiple symptoms in multiple organ systems. This is not only hard to manage, but it’s difficult to explain to others and for others to understand. Sometimes providers who haven’t been trained to identify autonomic disorders have a hard time understanding and are at a loss when comes to treating you.

Dysautonomia Is Not Well-Known: Doctors are not usually trained about autonomic disorders in medical school. (Although we are working hard to change that.) Finding a provider who understands dysautonomia and how to treat it is one of the greatest challenges patients face. It’s not uncommon for patients to be told it’s all in their head by a doctor who can’t explain the reason for their symptoms. Everybody knows what cancer is, so they have great empathy for cancer patients. But most people don’t know about dysautonomia which makes it hard for them to relate to the patient or understand the debilitating nature of autonomic disorders.

Invisible Illness: Because many symptoms of dysautonomia are invisible, it’s easy for people to look at dysautonomia patients and forget they are ill. It’s not uncommon for patients to hear statements such as, “But you don’t look sick. You look great.” The implication is that things can’t be that bad. Patients may feel like they shouldn’t share just how hard it is to manage their symptoms. They may feel pressure to “act” as healthy as they look. They may push themselves and overdo it to keep up with others and feel normal. This may make things worse or trigger other symptoms. Some patients may avoid social gatherings because it’s hard to pretend they are ok.

It’s easy to see why dysautonomia patients often feel alone, misunderstood, and frustrated. In managing their health, they must limit their activities. They often cannot do the same things other people do. Their life looks different as they miss out on school or work, extra-curricular activities, and social events. These changes limits contact with friends and family which can feel isolating. Their new way living may include having to rely on others for help with shopping, housework and driving. Many feel they have lost their own independence. Some patients may need help with the simple activities of daily living (showering, getting out of bed, toileting). They may feel like they are burden to others or all alone in their pain because everyone else is living life as usual. Loneliness is a significant factor in depression.

These are significant changes and adjustments for patients. No patient is to be faulted if they find it hard to navigate these changes while they deal with the pain of their symptoms. Temporary feelings of sadness are normal. But if you or a loved one are struggling for a couple of weeks, you should know the signs and symptoms of depression and suicidal ideation, so you can get help.

Sign of Depression:

Persistent sadness, anxiousness, or moodiness

Feeling hopeless, pessimistic, “empty inside”

Irritability, frustration, restlessness

Changes in sleep patterns and eating habits

Loss of interest or pleasure in usual activities or hobbies

Decrease in energy, fatigue

Loss of motivation at work or school

Difficulty concentrating, remembering, or making decisions

Changes in appetite or weight

Pulling away from friends or family members

Using alcohol or drugs to cope

Unnecessary risk taking

Not caring about personal appearance

Lack of response to praise

Tearfulness

Apathy, (lack of feeling, emotion, or expression)

Some of these symptoms can be associated with the illness itself which is why depression in the chronically ill is sometimes overlooked. Stigmas associated with mental health may cause a caregiver or patient to talk themselves out of taking these signs seriously.

A patient may be so depressed that they don’t even know how to reach out for help. If you are that patient and you don’t know how to talk to your provider or someone, send them the link to this article or print it, share it and say, “Can you help me?”

If it’s your friend or loved one who is depressed, they likely need someone to reach into their lives and offer help. You can be a lifeline to someone in need. It’s important to make sure these symptoms are discussed with their health care provider and if needed, a licensed mental health professional. Chronic illness may trigger depression, but ongoing depression can also make chronic illness worse. It can keep patients from seeking and trying new treatments and taking ownership of their health care. This creates a vicious cycle.

Depression affects the way someone thinks and their ability to see beyond their current situation. When someone is battling depression, they may not only focus on current difficulties but also all the negative outcomes or obstacles they’ve experienced in life. This is not something you can expect a person to “snap” out of or turn around with positive thinking. Depression needs treatment. If left untreated, depression can become despair and lead to suicidal ideation.

Signs of Suicidal Ideation:

Feelings of wanting to die

Fixation on death and dying

Direct expressions of desire to commit suicide: “I want to kill myself.” “I’m going to commit suicide.”

Talking about death or ways to die

Indirect hints: “I won’t be a burden for much longer.” “If anything happens to me, I want you to know…”

Giving possessions away.

Becomes suddenly cheerful after a period of depression. (This may occur once a person has finally made a plan to commit suicide.)

Journaling about suicide and death

Artistic expressions that focus on death: Writing songs or poems about death, paintings, or drawings

Statements like: “I’m scared of how I feel.” “I’m scared of what I might do.”

Writing a suicide note

Other statements: “This is too hard. I don’t think I can do this anymore.”

Talking about depression and suicide is never easy, but if you have a loved one or if you are struggling with depression, it is essential not to avoid it. If you are experiencing depression and suicidal ideation, call the Suicide Hotline. Dial 988 to speak to someone immediately. Tell a loved one and ask for help.

If you see any of the signs listed above in someone you know and love, it’s critical that you talk to them and get them help. If someone tells you they are considering suicide, it’s not up to you to determine if this a just a cry for attention or a real threat. Take the person seriously. If this is a crisis moment and the person is in immediate danger call 911.

How to approach a friend or loved one showing signs of depression:

- Talk to your loved one and tell them the changes you’ve seen in them and why you’re concerned. Try to use some specific examples. Avoid using statements that start with “You did this. You said this.” That may sound accusatory. Lead with “I” statements. “I noticed ____ happened, and it concerns me because I know how hard things have been for you lately…”

- Let them talk: Listen attentively. Acknowledge their feelings. Reflect back to them what you’re hearing for clarification.

- Let them know that depression is nothing to be ashamed of, and it’s not uncommon for people who are chronically ill. Depression is a medical condition and there are treatments.

- Offer to make an appointment with a professional or go with them to an appointment. Do not let them sweep this under the rug and ignore it. Hold them accountable to seeking help.

- Don’t promise confidentiality. You need to be free to reach out for help on behalf of this person.

- Ask direct questions about whether they have contemplated suicide.

If there are signs of suicidal ideation:

Ask if they’ve made a plan. This can be hard to do and the answer hard to hear, especially if you’re talking to your child or a close family member. Remaining calm and not reacting out of fear will help your loved one as they open-up and share. They may be feeling shame and embarrassment. They may be afraid of your reaction. Create an emotionally safe environment for them. If they can’t or don’t want to share, do not pressure them to talk.

Do not leave them alone. Contact a friend or family member to come be with you and your loved one as you plan the next steps.

Remove dangerous objects: Keep potentially harmful objects locked up or away from the individual (this includes medicine and alcohol).

Take the person to get help: Go to the nearest emergency room, contact a mental health professional, or call 911 immediately.

Mental Health Support

If you or a loved one is living with dysautonomia or another chronic illness, recognize that chronic illness, disabilities, and depression can become a debilitating and dangerous cycle. Whether you’ve been dealing with this illness for a long time, or you’ve just been diagnosed, you may want to consider finding a mental health counselor to help you navigate the psychological impact of living with chronic illness. Having a trained professional to help you mange stress, find coping skills, and provide a safe place to share your emotions and struggles may be a missing and valuable piece of the treatment plan.

Suicide Hotline: Dial 988 or 1-800-SUICIDE

Crisis Textline: Text HOME to 741741 from anywhere in the US at any time. A live, trained crisis counselor receives the text and responds, all from a secure online platform. https://www.crisistextline.org/

National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI): Peer Support (727) 600-5838

Help Line (800) 950-NAMI (6264).

Crisis Center of Tampa Bay (Dial 2-1-1)

Veterans Crisis Line: 1-800-273-8255 and press 1

https://www.veteranscrisisline.net/

If you are a health care provider or work with patients with chronic illnesses consider taking the Mental Health First Aid Course (MHFA) offered by one of our community partners, LOVE IV LAWRENCE. Mental Health First Aid is a course that teaches how to identify, understand and respond to signs and symptoms of mental health challenges and substance use disorders. The training gives you the skills needed to reach out and provide initial help and support to someone who may be developing a mental health or substance abuse problem or experiencing a crisis. For more information: Mental Health First Aid Course (MHFA)

Related Articles

One Response

It was hard enough to lose what I loved most: Taekwondo. I used to have recurring nightmares the first few years that I took classes; I would dream that someone was attacking me, but I couldn’t fight back because my movements were in slow motion. Now it’s real; I try to run, but it’s like there’s an 80 mph wind in my face. Walking feels so hard, and I worry that people will think I’m drunk. But what’s hardest is hearing my husband say he is sick of “all of it,” that I don’t do enough to pull my weight, that the house isn’t clean enough… I’m doing the best I can, but I have no one. I wanted to join an in-person support group, but there aren’t any near me, and I can’t drive for more than 30 minutes. I’m thinking about starting a support group for the chronically ill, but I don’t know how to begin.